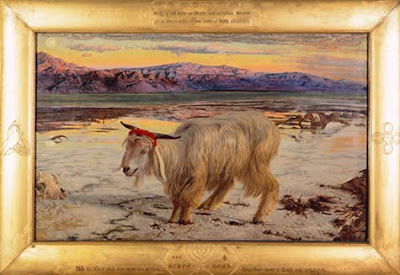

Tim Challies posted a powerful quote from Ligon Duncan, though I think originally from R. A. Finlayson:

Tim Challies posted a powerful quote from Ligon Duncan, though I think originally from R. A. Finlayson:Hell is eternity in the presence of God without a mediator.

Heaven is eternity in the presence of God, with a mediator.

The following article of mine was originally published in the Evangelical Magazine

Ask an evangelical Christian to define Hell and they may well say “Hell is separation from God.” What they may mean is that Hell is a place where God is not present. Ask them if Jesus was separated from his Father in the dark hours in which he suffered on the cross and they will say that he was separated from God, that his Father abandoned him and turned his face away from him. Hell means separation from God, and the cross, for Christ, meant separation from God.

However, ask them if Hell is a place, a part of creation, and they will agree that it is. Ask them if God is omnipresent, present in and to the whole creation, and they will want to affirm that too. So if Hell is a place, a part of creation, then God must be present in Hell. If he is present in Hell then how can we speak of Hell as separation from God? If we imagined Hell to be an isolated dumping ground, a far off corner of the universe where God is absent, where people have chosen to exist without him and been given over to those desires, then we are no longer thinking clearly of God as omnipresent.

The reason why we think of Hell as separation from God is, I suspect, because Jesus readily uses that language to describe the misery of eternal punishment. After all will he not say “I never knew you, depart from me, you workers of lawlessness,”? (Matt. 7:21-23). Will he not on the last day, as the enthroned King, say to those on his left “depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire” (Matt. 25:41). Are we not right to think of Hell as exclusion from God's presence, and therefore as a state of separation from him? Before giving a fuller answer to that question we ought to consider some of the strands that make up the biblical teaching about the presence of God.

God is omnipresent

The Bible affirms the omnipresence of God. God is infinite. With regard to space he is immense, having no “no-go” areas from which he is excluded. He is not contained in his creation, or limited by its dimensions in any way. Heaven and earth cannot contain him. This is what Solomon acknowledges at the dedication of the temple “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Behold, heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you; how much less this house that I have built! (1 Kings 8:27). God testifies to this same truth through Jeremiah, saying “Am I a God at hand, declares the LORD, and not a God far away? Can a man hide himself in secret places so that I cannot see him? declares the LORD. Do I not fill heaven and earth? declares the LORD (Jer. 23:23-24). Psalm 139:7-10 is also relevant here:

Where shall I go from your Spirit? Or where shall I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there! If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there! If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there your hand shall lead me, and your right hand shall hold me.

Amos makes the same point in the context of those seeking to escape God's judgment (Amos 9:1-4). Paul told even the idolatrous Athenians that God was not far from them, and that in him they lived, moved and had their being (Acts 17:24-28).

Sinners are said to depart from God's presence

Even though God's omnipresence is affirmed the Bible freely uses language about people departing from, or being sent away from God's presence. This is Cain's fear, as God's face will then be hidden from him (Gen. 4:14). Two verses later we are told that Cain went away from the presence of the Lord and lived in the land of Nod. It was to be Israel's experience to be sent away from God's presence for persistent disobedience and idolatry (Jer. 7:15; 15:1; 23:39). Jeremiah announces the climatic judgment against Jerusalem in this way (52:3-4):

It was because of the LORD's anger that all this happened to Jerusalem and Judah, and in the end he thrust them from his presence...So in the ninth year of Zedekiah's reign, on the tenth day of the tenth month, Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon marched against Jerusalem with his whole army. They camped outside the city and built siege works all around it.

Judah and Jerusalem suffer the same consequences as Israel previously had known. As 2 Kings 17:18-23 says, “the LORD was very angry with Israel and removed them from his presence...he afflicted them and gave them into the hands of plunderers, until he thrust them from his presence...the Israelites persisted in all the sins of Jeroboam and did not turn away from them until the LORD removed them from his presence.”

Conversely there are numerous references that speak of God's presence, many of them bound up with the tabernacle and temple, that speak of God's presence in distinctly local ways. It ought to be remembered that heaven is specifically God's dwelling place, and that he is especially said to be present there.

In addition to the language of being removed from God's presence we can add that of separation. Here we are confronted with Isaiah's famous words (Isa. 59:2), “but your iniquities have separated you from your God; your sins have hidden his face from you, so that he will not hear.”

Given these distinct ways of speaking about God's presence in Scripture we should not make the mistake of playing them off against each other as if they were in conflict in any way. Furthermore, we ought to be careful about how we receive this language and not slip into wrong thinking because of certain connotations implied by the language of departing from God's presence, or being separated and sent away. In one sense God was as much present to Cain in Nod as he was to Adam in the Garden and as he is now to you as you read this. None of the exiles saw a sign that read “Welcome to Babylon, God ain't here!” I suspect that it is simply carelessness and imprecision of thought that leads us to think of Hell as separation from God in spatial terms.

Understanding God's spatial and relational presence

So how should we understand the language of departing from God's presence? Not in spatial, but in relational terms. Or, to put it another way, it is a spiritual separation that we experience because of our sin, not a strictly local separation. Although the church in its infancy did experience God's presence in connection with holy places this experience is abrogated by the coming of Christ (John 4:20-24. That is not to deny the present dwelling of the covenant God among his people by the Spirit, but it is to say that this dwelling is not associated with geographic places. Even so this was well understood by Solomon, who knew full well that event though God would dwell in the temple even the highest heavens could not contain him (1 Kings 8:27; cf. Isa. 66:1-2, Acts 7:47-50). So the language of drawing near and departing from God's presence isn't a matter of physical distance but of his relationship to us. Our sin creates an ethical distance not a geographical one. We know in a limited way from our own experience that we can be in the same room as someone physically, but if we have fallen out with them it is like we are a million miles apart. So Isaiah says that on account of Israel's sins God had hidden his face from them (Isa. 59:2; cf. Num. 6:25).

God's presence in relation to Hell and the atonement

Is God present in Hell? We have to say that he is. Firstly, because Scripture affirms that he is. In Hell there is torment day and night in the presence of the holy angels and the in the presence of the Lamb (Rev. 14:9-11). Secondly, to deny that he is present in all of his creation is to deny that God is infinite and immense. Was God present at the cross when Christ was forsaken? He was spatially as present in Jerusalem then as he is today. Nevertheless in a way that we cannot comprehend but which is the cause of all our hope in time and eternity, we believe that the Son of God knew all the torments of a condemned sinner, and all the relational distance that guilty sinners will receive. His experience of being forsaken was not imagined (Mark 15:33-34). In that cry of dereliction he knew abandonment, as Christ the only true and perfect covenant keeper, bore the full weight of the covenant curses in the place of his people (Gal. 3:10-14).

When we turn to the Westminster Larger Catechism question 29, which deals with the subject of God's relationship to those who will experience future judgement in Hell, we find a precision of thought on these matters that is often lacking today:

Q. 29. What are the punishments of sin in the world to come?

A. The punishments of sin in the world to come, are everlasting separation from the comfortable presence of God, and most grievous torments in soul and body, without intermission, in hell-fire forever. (emphasis added)

Hell is not spatial separation from God, it cannot be because God is omnipresent. No, Hell is separation from the comfortable presence of God. It is the unshielded experience of the presence of God in his holiness and just wrath, and the absence of his mercy and grace.