Tuesday, December 24, 2013

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Douglas Alexander on the persecution of Christians in the Middle East

Following on from comments made by Prince Charles about the persecution of Christians in the Middle East it is good to see this from Douglas Alexander, Labour Shadow Foreign Secretary:

“Across the world, there will be Christians this week for whom attending a church service this Christmas is not an act of faithful witness, but an act of life-risking bravery. That cannot be right and we need the courage to say so.”You can read more from him in The Telegraph

Sunday, November 17, 2013

The Primacy of Narrative Theology

In The Triune God: An Essay in Postliberal Theology, William Placher briefly makes the case for the primacy of narrative theology:

Of course, the Bible contains more than stories--hymns, sermons, theological essays, laments, laws, and prophecies...It is a complex collection of books, and no one category can do it justice. Nevertheless the category of "story" or "narrative" does seem to have a certain priority: it seems more important to say, of each of the other biblical genres, that they derive part of their meaning from their relation to an overarching story than the other way round.The Triune God, p. 46

It seems a fair point. All the action on the stage involves a script, and the both the little stories and big story have narrators who are telling the story (all of which means that narrative theology must go hand in hand with speech acts).

Narrative theology only has real primacy if and when the "Narrator" with a capital "N" is telling the story and speaking within it. Or, in other words, you can't really have narrative theology without the Canon, Inspiration, and Inerrancy all being woven indelibly into the story.

Besides which the devil has his own version of narrative theology (Gen. 3; Matthew 4:1-11), with an alternative script, plot line, principal actors and closing scenes.

Thursday, November 14, 2013

Theological comedy

Not many theological books raise a chuckle, some can barely manage a snort, although I do remember laughing out loud whilst reading N T Wright's Who was Jesus? whilst sat on a train at Gloucester station. Down through the years, perusing book after book, the gags have been few and far between.

Until yesterday, when this, from William Placher, raised a smile...

After I had written a first draft, though, I realized to my surprise how often I had cited Hans Urs von Balthasar at key junctures. I do not know what it means for a pragmatic, midwestern American Presbyterian to be so influenced by a Catholic who said he drew his most important insights from a woman mystic who claimed to have received the stigmata, but there it is.William Placher, The Triune God, p. x

Friday, November 08, 2013

The Bonfire of Reformed Identities

Nothing if not provocative, Peter Leithart has a post on 'The End of Protestantism' that is more than a little subversive. With apologies to David Wells this is The Courage to be

Posts about who gets to define what Reformed means are like buses. You wait ages for one and then come come along at the same time.

Kevin De Young's post widens what it means to be Reformed to include a larger subset of Calvinistic evangelicals, whilst on the other hand Peter Leithart's extends the boundaries of what it means to be and act as a Reformed Christian in a Romeward direction (but without endorsing the obvious Roman bits of theology and practise).

You can also read Scott Clark's response to Leithart here

Thursday, November 07, 2013

The Holy Spirit, the Father and the Hypostatic Union

One of the refreshing things about reading long dead writers is that, bizarrely, they can help you to look at familiar things with fresh eyes.

Take the following observation by Augustine on the Trinity. In context he is launching out on his discussion of whether 'sending' (the missions of the Son and Spirit) implies inferiority.

He has this telling remark about the status of the Spirit:

The Holy Spirit too, therefore, is said to have been sent because of these bodily forms [a dove, fire] which sprang into being in time in order to signify him and show him in a manner suited to human senses.

But he is not said to be less than the Father as the Son is on account of his servant form. That form was attached in inseparable union to his person, whereas these other physical manifestations appeared for a time in order to show what had to be shown and then afterward ceased to be.De Trinitate, Book II:3:1 (emphasis added)

All of which chimes with what we see and read in the gospels. No forgiveness for those who commit blasphemy against the Spirit, whereas there will be for those who speak against the Son of Man.

The Son's 'sending' is tied to the union of his Godhead to his perfect humanity, and therefore to his estate of humiliation. But the nature of the outward manifestation of the Spirit's presence did not involve his union with created things, 'he did not join them to himself and his person to be held in an everlasting union' (De Trin. Book II:2:6).

For Augustine there it is clear that we will not understand how Scripture presents the Son of God unless we realise the distinctiveness of the Son's redemptive mission and his relationship to the Father. Thus the Son is spoken of:

1. In the form of God

2. In the form of a servant

Beautifully outlined and elaborated in Book 1:4.

Even so Augustine adds a third interpretative rule to include texts that speak of the Son:

3. As from the Father

What happens when we fail to follow this rule?

Augustine divides interpreters into those who are culpable in treating the Son as less than the Father ontologically (think Aians), and those who 'are no so learned or so well versed in these matters, and try to measure these texts by the form-of-a-servant rule' and find that 'it is very upsetting when they fail to make proper sense of them'. He goes on:

To avoid this, we should apply this other rule, which tells us not that the Son is less than the Father, but that he is from the Father. This does not imply any dearth of equality, but only his birth in eternity. (De Trin. Book 2:1:3)Ah, so you end up having to confess the eternal generation of the Son to make sense of certain texts (e.g. John 5:26). How very Niceno-Constantinopolitan of him. Or as Father Ted would say, 'that would be an ecumenical matter'.

Tuesday, November 05, 2013

The tangled question of theophanies

Augustine is regarded as a kind of a bogey man by some for his movement away from identifying Old Testament theophanies as manifestations of the incarnate Christ, breaking an interpretative tradition that extended from Justin Martyr on.

Augustine was hardly unaware of this tradition (De Trin. Book II:2:8):

Take some words spoken by God in one of the prophets: Heaven and earth do I fill (Jer. 23:24); if they are ascribed to the Son--and it is he, so a number of authors prefer to think, who spoke to and through the prophets...

There is even a prophecy of Isaiah in which Christ himself is to be understood as saying about his future coming, And now the Lord, and his Spirit, has sent me (Is 48:16)Why then the departure from this tradition?

Is it as crude as the accusation made by the late Colin Gunton that an 'anti-incarnational platonism is to be found in Augustine's treatment of the Old Testament theophanies'?

Gunton was sharply critical of Augustine on this point. The breach with the tradition was emblematic of a deeper theological fissure opening up between the relationship of the creature and the Creator, a widening that has serious implications for taking Augustine as a reliable theological guide on the trinity at all:

In place of the tradition, going back to Irenaeus, of the Father relating to the world by means of the Son and Spirit, we are in danger of supposing an unknown God working through angels. Augustine's shying away from the involvement of God with the material order should be contrasted with the more concrete modes of speech of both Irenaeus and Tertullian.'Augustine, the Trinity and the Theological Crisis of the West' in The Promise of Trinitarian Theology, p. 34-35

But for Augustine 'divinity cannot be seen by human sight in any way whatever' (De Trin. Book I:2:11), and therefore he was sensitive to the view that invisibility was predicated only of the Father, and not of the Son. The invisibility of the Son, connected as it is with his essential divine nature, is something that Augustine was zealous to safeguard. In fact there may be some evidence that this theological lacuna, namely that of the invisible Father and visible Son, stemmed not only from the tradition but also, and perhaps more pertinently so, from the Manichaeism that Augustine had escaped from.

Furthermore, Augustine wanted to do justice to the primacy of the biblical language of 'sending' and 'sent' being tied to the historical reality of the incarnation, and not to previous manifestations and theophanies.

On other matters, such as whether and how we can identify particular persons with particular theophanies (after all, aren't the outward signs at Sinai also evident at Pentecost? Could not the Spirit have therefore manifested his presence at the giving of the Law?), Augustine was prepared to be agnostic if the evidence was not persuasive enough.

Sorting out what the great bishop and doctor of grace called 'this tangled question' of the persons manifested in the Old Testament theophanies is something that I will defer to later posts. It would be a great help to find out whether Augustine paid any attention to the ghost of Plato looking over his shoulder as he wrote, and, as ever, it is best to assess him based on his own words as he unfolds his case.

Then Face to Face

In De Trinitate Augustine interprets the handing over over the kingdom to the Father as not only the culmination of the mediatorial reign of the Son of Man but as resulting in the eternal blessedness of the saints: seeing God face to face.

For Augustine, the reality of the Son of Man in the judgement, a visible glory seen by the righteous and the wicked, it is surpassed by the glory that will exclusively be beheld by those who inherit the kingdom:

This contemplation is promised us as the end of all activities and the eternal perfection of all joys

It is of this contemplation that I understand the text, When he hands over the kingdom to God and the Father (1 Cor 15:24), that is, when the man Christ Jesus, mediator of God and men (1 Tim 2:5), now reigning for the just who live by faith (Heb 2:4), brings them to the contemplation of God and the Father.

Contemplation in fact is the reward of faith, a reward for which hearts are cleansed through faith...

For the fullness of our happiness, beyond which there is nothing else, is this: to enjoy God the three in whose image we were made.De Trinitate, Book 1:3:17-18

The Trinity: Mysteries and Mistakes

As well as suggesting that there should be different types of books to help all sorts of people to understand the truth, Augustine, it comes as now surprise, had lots of wise things to say about the search for the truth in faith's quest to understand the trinity.

Unless some sense of the sheer infinitude of the reality before us dwarfs our attempts to gain comprehension of the truth we haven't even begun to understand anything about God or ourselves:

People who seek God, and stretch their minds as far as human weakness is able toward an understanding of the trinity, must surely experience the strain of trying to fix their gaze on light inaccessible (1 Tim. 6:16), and on the difficulties presented by the holy scriptures in their multifarious diversity of form, which are designed, so it seems to me, to wear Adam down and let Christ's glorious grace shine through.

So they should find it easy, once they do shake off all uncertainty on a point and reach a definite conclusion, to excuse those who make mistakes in the exploration of deep a mystery.

But there are two things which are very hard to tolerate in the mistakes people make:

presumption, before the truth is clear

and

defense of the false presumption when it has become so.

No two vices could be more of a hindrance to discovering the truth or handling the divine and holy books.De Trinitate, Book II:1

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

When does heresy become heresy?

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

We know now there is nothing left to fear

Sinclair Ferguson's sermon 'Can I fully trust you?' on the 23rd Psalm can be found here

It repays careful listening.

Monday, October 21, 2013

The cross has little place in your preaching

Iain Murray recounts a fascinating criticism made of Lloyd-Jones' preaching in the late 1920s. It was made by a fellow minister when Lloyd-Jones was preaching at a service in Bridgend, South Wales. Here's the substance of what the Bridgend minister said:

'...you talk of God's action and God's sovereignty like a hyper-Calvinist, and of spiritual experience like a Quaker, but the cross and the work of Christ have little place in your preaching.'D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones: The First Forty Years 1899-1939, p. 190-191 (emphasis added)

The observation it seems was true.

Lloyd-Jones, speaking at a later date (Murray doesn't indicate when), spoke of how he was like George Whitefield in his early evangelistic preaching, strongly emphasising sin and the rebirth and, intriguingly, saying the following:

'I assumed the atonement but did not distinctly preach it or justification by faith. This man set me thinking and I began to read more fully in theology.'Murray comments that this remark 'was to prove of considerable importance in the development of Dr. Lloyd-Jones' ministry.' In the following paragraphs Murray makes two important points:

The criticism which he heard in Bridgend was thus a fruitful incentive to further thinking.

In particular, he concentrated upon the doctrines specified by his critic.To remedy this lacunae in his theology Lloyd-Jones sought the guidance of Rev. Vernon Lewis (who regarded the Doctor's preaching as similar to Karl Barth's). Lewis recommendations included the works of P. T. Forsyth, James Denney and R. W. Dale.

Several things need to be born in mind in analysing this episode, and in particular the blend of the personal and the cultural.

Lloyd-Jones was not seminary trained. One could argue that the gaps in his theology were never plugged prior to his entering the ministry, and therefore were only exposed and rectified a few years into his first pastorate. There is an element of truth in this, although it must be remembered that his burning desire was to be an evangelist in a poor area through the agency of the 'Forward Movement' and its mission halls, the evangelistic wing of the Presbyterian Church of Wales (which of course is what happened).

Even so, had he gone to the denomination's theological training college in Aberystwyth it is far from certain that he would have received an orthodox, confessional education.

From the vantage point of early 21st Century evangelical theology, the plain fact is that there are greater theological resources available, institutionally through seminaries, publishers, model preachers, conferences, and much of it mediated the internet, than Lloyd-Jones ever had at his disposal.

Yet, for all the gains in the evangelical world that have massively strengthened our grasp of the cross and the work of Christ, one wonders whether the personal narrative of individuals as their theological deficiencies are discovered are treated with the same eye to growth and development as this episode indicates. Look again at the key words: 'the cross and the work of Christ have little place in your preaching'...'I assumed the atonement but did not distinctly preach it or justification by faith'.

It would have been easy, as a hearer, to dismiss Lloyd-Jones, and even to rail against his deficient theology, and that in our time from a much more influential platform of social media.

Lloyd-Jones' response is also instructive. His response to this criticism was to take it to heart. To think it through, to think more deeply, to consult, to read, to study, to rectify what was lacking, and to do that with lesser resources than we posses today.

Unexplored influences on Lloyd-Jones: The Vision of God

It is relatively straightforward to identify not only the theological influences that shaped the life and ministry of Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, but also how and when he came into contact with them.

His church heritage was that of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist fathers of the 18th Century, an atmosphere that shaped his whole spirituality (the two volume work Tadau Methodistiaid, was, writes Iain Murray, constantly in his hands in his early years at Sandfields, Aberavon).

Then there is the specific life-long impact made when he found the two volume 1834 edition of Jonathan Edwards' works in a bookshop in Cardiff in 1929, through to his discovery in Toronto, in 1932, of the ten volumes of B. B. Warfield (although some seventeen years later he acknowledged that reading Warfield had left him unbalanced).

To this we can add his reading of an advertisement for a new edition of The Autobiography of Richard Baxter (in the 8th October 1925 edition of The British Weekly), which lead him to read F. J. Powicke's biography of Richard Baxter, and to a lifelong love of the Puritans. As a wedding present in early January 1927 he was given second hand sets of the works of John Owen and Richard Baxter.

All of these influences are well known and well explored. But the following anecdote from Iain Murray is, as far as I am unaware, unexplored. In his own words Lloyd-Jones acknowledges the impact of Kenneth Kirk's The Vision of God.

Another major work which he read about this period [early 1930s] was The Vision of God by Kenneth E. Kirk, being the Bampton Lectures for 1928, delivered at Oxford where Kirk, nine years later, became Bishop.

'These lectures,' he commented later, 'had a great effect on me. Kirk dealt with the pursuit of God and the different methods by which men have sought God, but he did it historically and went right through -- the medieval mystics, the later mystics and so on.

I found that book absolutely seminal. It gave me a lot of background. It made me think. It helped me to understand the Scriptures and also see the dangers in such movements as monasticism and the anchorites.

I regard The Vision of God as one of the greatest books which I ever read.'D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones: The First Forty Years 1899-1939, p. 254

It is not clear from the text exactly when Lloyd-Jones made the comments above. Perhaps it was during the period from 1961 when Iain Murray was intermittently accumulating information, or as late as 1980.

I am not aware of any significant secondary impact made by this book, comparable to that of Lloyd-Jones' commendation of the works of Edwards, Owen, Warfield, or the Tadau Methodistiaid.

Moreover, I am not aware of any conference address or article that has traced any of the impact of this work either in the sermons and addresses, or the published volumes by the Doctor. But clearly it did made a significant impact upon his thinking, and it would be interesting to excavate the details of it.

And, as it happens, I came across The Vision of God at Cardiff University Library just two weeks ago.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

The frenzy of heretics made them necessary

The following extract from Hilary of Poitiers' letter "On the Councils" to the Western bishops in 359 AD makes good theological and pastoral sense:

Every separate point of heretical doctrine has been successfully refuted. The infinte and boundless God cannot be made comprehensible by a few words of human speech.

Brevity often misleads both learner and teacher, and a concentrated discourse either causes a subject not to be understood, or spoils the meaning of an argument where a thing is hinted at, and is not proved by full demonstration.

The bishops fully understood this, and therefore have used for the purpose of teaching many definitions and a profusion of words that the ordinary understanding might find no difficulty, but that their hearers might be saturated with the truth thus differently expressed, and that in treating of divine things these adequate and manifold definitions might leave no room for danger or obscurity.

You must not be surprised, dear brethren, that so many creeds have recently been written. The frenzy of heretics makes it necessary.

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Can we be Trinitarian without being Nicene?

For all the desire that we possess to be purely biblical in the categories and language that we use to express our doctrinal convictions I am not aware of anyone today who is significantly and successfully Trinitarian who does not owe a great and decisive debt to the Council of Nicaea.

That the Nicene Creed is woven indelibly into the fabric of contemporary, orthodox, theology is an undeniable and persistent fact. It is a permanent legacy in the articulation of the doctrine of God's triune identity.

Quite simply, can we be Trinitarian without being Nicene? I seriously doubt it.

To attempt it would be a crazy feat of theological gymnastics, an oddball mission to bungee-jump into the world of the New Testament without stopping anywhere in the following twenty centuries of church history.

Even if it were possible to do so the undeniable reality is that in order to secure clarity on the biblical meaning of God's eternal triune being, and crucially to distinguish this architectonic truth from it's heretical rivals, it proved necessary to use extra-biblical terminology.

There is a recognition in the church fathers that heretics use the same biblical stock of language as the orthodox but give these words a false meaning. How else could they distinguish truth from error, orthodoxy from heresy, Athens from Jerusalem, without the painstaking task of clarifying the meaning of biblical terms by employing a wider theological vocabulary?

Their legacy has shaped the theology and language of churches across the globe ever since.

Monday, September 02, 2013

As true as ever it was

"You will never find Jesus so precious as when the world is one vast howling wilderness. Then He is like a rose blooming in the midst of the desolation,

–a rock rising above the storm."

Robert Murray M'Cheyne

Monday, August 26, 2013

Wednesday, August 07, 2013

Christ in the OT: Present or Absent?

There are several options open to exegetes when grappling with the real presence or absence of Christ in the OT:

A) Christ was ontologically present (ruling, leading, saving, speaking to his people) but cognitively absent.

In other words he ruled, lead, saved and spoke to his people, but was The Jesus They Never Knew, as he was never revealed to them, or never revealed himself, as their Saviour-King. The self-revealing of distinct persons of the Godhead being a matter that omitted from the revelation granted to the OT saints (although many exegetes would allow for puzzling, cryptic hints at plurality. Therefore he was not personally addressed by his people in their prayers, was never the object of their worship, obedience, trust etc.

The tension between presence and absence can be explained from a variety of theological perspectives on a spectrum extending from liberal to conservative. More on this in later posts.

B) Christ was ontologically and cognitively present to his people.

Pre-Augustine it was common to understand OT theophanies as the appearance of the Son of God to his people (a point made by H. P. Liddon in the Bampton Lectures on The Divinity of our Lord, 1866).

Manlio Simonetti underlines this in two footnotes in his Biblical Interpretation in the Early Church:

Following a tradition going back to the 2nd Century, Eusebius takes the Logos, the Son of God, as the object of these [appearances of God to the patriarchs and Moses], rather than God the Father. (n. 3, p. 83)

Theophilus' one concern is to make it clear that the one who walked in Paradise and spoke with Adam, was not God the Father, but his Son, the Logos, the subject of all the Old Testament theophanies. (n. 20, p.33)That the early church fathers understood the texts in this way is clear, why they read them in this way is another matter, and why many contemporary conservative evangelical scholars are averse to interpreting the texts in the same way is an intriguing question to pose.

Saturday, August 03, 2013

A sentence that smacks you in the head

To read the early church fathers is to immerse oneself into a world of theologians, preachers, and worshippers who were saturated in the Scriptures. Whatever we make of their exegetical methods, speculations, and odd pre-occupations, they self-consciously based their thinking upon the authority of the sacred text of the Word of God. Athanasius wrote that "The holy and inspired Scriptures are fully sufficient for the proclamation of the truth."

Whatever else may wish to discern as factors in their thinking (Hellenic allegorical methods of interpretation, strains of Platonic and Neo-platonic philosophy etc.) there can be no doubt as to their starting point; a point well recognised by O'Keefe and Reno in their refreshing primer Sanctified Vision: An Introduction to Early Christian Interpretation of the Bible:

How many times must we read and teach Origen's On First Principles, a dauntingly speculative inquiry into the nature of God, the world, human existence and destiny, before noticing that the opening sentence stipulates that the Bible is the sole source of wisdom?

To see that sentence and understand its meaning is like receiving a blow to the head.And to save you googling it, here is that sentence (and for good measure the one after it):

All who believe and are assured that grace and truth were obtained through Jesus Christ, and who know Christ to be the truth, agreeably to His own declaration, “I am the truth,” derive the knowledge which incites men to a good and happy life from no other source than from the very words and teaching of Christ.

And by the words of Christ we do not mean those only which He spake when He became man and tabernacled in the flesh; for before that time, Christ, the Word of God, was in Moses and the prophets. For without the Word of God, how could they have been able to prophesy of Christ?

Monday, July 29, 2013

The Hymn Police and the Editing of God's Holiness

Timothy George has a helpful short article on the 'problem' of the holy love, justice and wrath of God:

Sin, judgment, cross, even Christ have become problematic terms in much contemporary theological discourse, but nothing so irritates and confounds as the idea of divine wrath. Recently, the wrath of God became a point of controversy in the decision of the Presbyterian Committee on Congregational Song to exclude from its new hymnal the much-loved song "In Christ Alone" by Keith Getty and Stuart Townend.

The Committee wanted to include this song because it is being sung in many churches, Presbyterian and otherwise, but they could not abide this line from the third stanza: "Till on that cross as Jesus died/the wrath of God was satisfied." For this they wanted to substitute: "…as Jesus died/the love of God was magnified." The authors of the hymn insisted on the original wording, and the Committee voted nine to six that "In Christ Alone" would not be among the eight hundred or so items in their new hymnal.You can read the whole thing ("No Squishy Love") here

The Creedal Imperative: G. L. Prestige

G. L. Prestige on the cause of creed making in the early church:

A thinking Church, a Church that professes to love God with all its mind as well as with its heart, cannot be content to lie for ever in an intellectual fallow. Circumstances no less than duty force it to interpret its convictions.

It is often repeated that the creeds are signposts against heresies -- that is to say, that the need for precise formulation of Christian belief arose from the circulation of misunderstandings and the prevalence of false interpretations. Though partly, that is not wholly true.

The creeds of the Church grew out of the teaching of the Church; the general effect of heresy was rather to force old creeds to be tightened up than to cause fresh creeds to be constructed.From Fathers & Heretics, p. 3

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Loving God above all

From Augustine:

'What is the object of my love?' I asked the earth and it said: 'It is not I.'

I asked all that is in it; they made the same confession. I asked the sea, the deeps, the living creatures that creep, and they responded: 'We are not your God, look beyond us.'

I asked the breezes which blow and the entire air with its inhabitants said: 'Anaximenes was mistaken; I am not God.'

I asked heaven, sun, moon and stars; they said: 'Nor are we the God whom you seek.'

And I said to all these things in my external environment: 'Tell me of my God whom you are not, tell me something about him.'

And with a great voice they cried out: 'He made us.'Confessions, 10.9.

My question was the attention I gave to them, and their response was their beauty.'

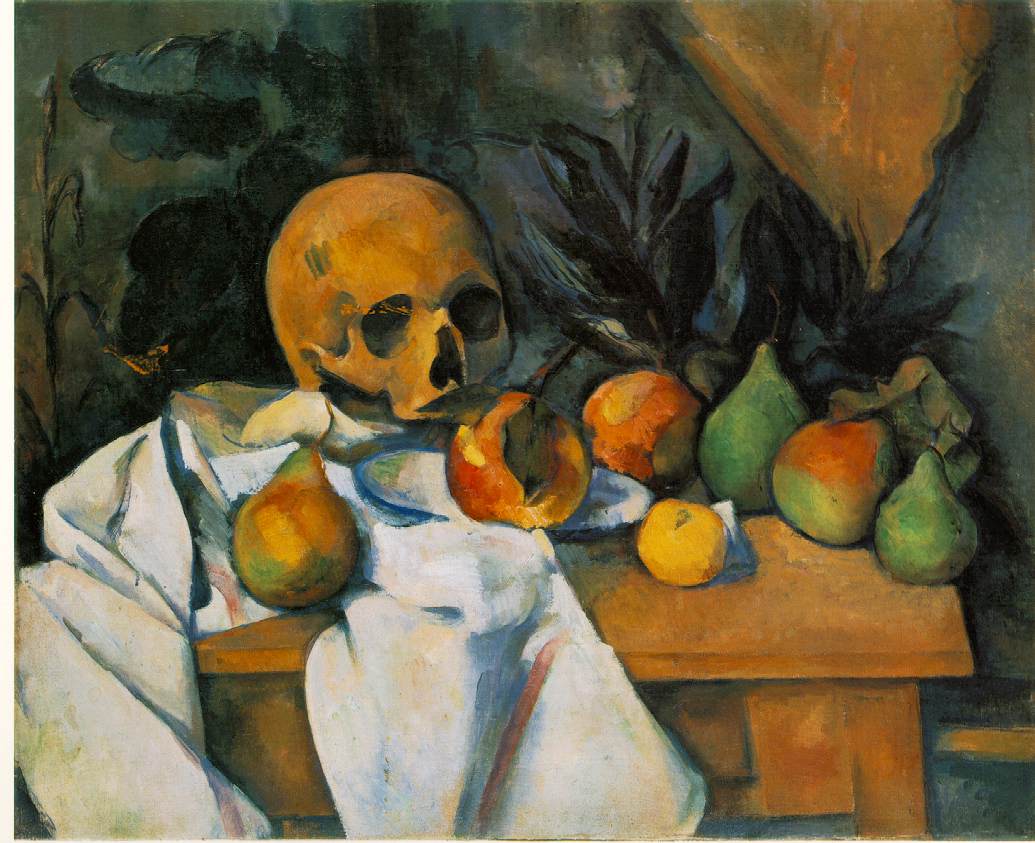

The sure path to idolatry

More from Weinandy on Athanasius:

This falling away from the vision of the good inevitably led human beings, Athanasius argues, to idolatry. Having become consumed with earthly and bodily pleasures, human beings lost all vision of the heavenly reality.

The soul no longer 'sees God the Word...after whose [likeness] (lit. 'after whom') she is made; but having departed from herself, imagines and feigns what is not' (8.1).

'Truth' and 'goodness' are now solely, but falsely, perceived in the visible and earthly. Thus human beings 'made gods for themselves of things seen, glorifying the creature rather than the Creator, and deifying the works rather than their Cause, Fashioner and Master' (8.3).Athanasius, A Theological Introduction, p. 16

Monday, June 24, 2013

Shutting out the atmosphere of eternity

What is sin?

It is the narrow, temporal, pursuit of pleasure, significance, and security, without and against our good Creator and Father

In his analysis of Athanasius' Contra Gentes, Thomas Weinandy's makes some perceptive comments about sin and desire. Listen to the notes that he strikes...pleasure, anxiety, security, temporality, delusion:

Sin, for Athanasius, is the turning away from God and all that pertains to him and a lustful self-centred turning inward to what pertains to man and his earthly bodily life with all its sensual pleasures. Sadly, human beings became 'habituated to these desires, so that they were afraid to leave them' (Contra Gentes, 3.4). Thus the soul anxiously feared death for in death all bodily lust and pleasures ceased. (Athanasius: A Theological Introduction, p. 15)

For sin, to Athanasius' mind, is more than a turning toward and seeking after the sensuous things of the world; rather these are but symptoms of human beings being more concerned about themselves than they are about God. (p. 17)

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Still doing good

It is personally heartening to see my book Risking the Truth being recommended in the Spring 2013 edition of the Western Seminary Magazine. The whole issue is on the subject of 'Contending for the faith without being contentious' and can be found here.

Against the Trinity

"It cannot escape observation that scarcely a heresy ever appeared which did not, when carried out to its logical results, come into collision with the doctrine of the Trinity at some point.

Through the whole history of opinion, the ever-recurring fact presented to us is that, however a man may begin his career of error, the general issue is that the doctrine of the Trinity, proving an unexpected check or insurmountable obstacle in the carrying out of his opinions, has to be modified or pushed aside; and he comes to be against the Trinity because he has found that it was against him."

George Smeaton, The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit, p. 5

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

The Folly and the Wisdom

Basil of Caesarea recounting his conversion:

—“I had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all my youth in vain labours, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish. Suddenly I awoke as out of a deep sleep. I beheld the wonderful light of the gospel truth, and I recognised the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world. I shed a flood of tears over my wretched life, and I prayed for a guide who might form in me the principles of piety.”

Thursday, May 30, 2013

God incarnate

Some brilliant comments all the way from the fourth century, courtesy of Hilary of Poitiers in Book Three of De Trinitate:

A virgin bears; her child is of God.

An infant wails; angels are heard in praise.

There are coarse swaddling clothes; God is being worshipped.

The glory of his majesty is not forfeited when he assumes the lowliness of flesh.

He who upholds the universe, within whom and through whom are all things, was brought forth by common childbirth;

He at whose voice Archangels and Angels tremble, and heaven and earth and all the elements of this world are melted, was heard in childish wailing.On understanding the eternal relationship between the Father and Son he says:

The Invisible and Incomprehensible, whom sight and feeling and touch cannot gauge, was wrapped in a cradle...He by whom man was made had nothing to gain by becoming man; it was to our gain that God was incarnate and dwelt among us.

...the proper service of faith is to grasp and confess the truth that it is incompetent to comprehend its Object.

If anyone lays upon his personal incapacity his failure to solve the mystery, in spite of the certainty that Father and Son stand to each other in those relations, he will be still more pained at the ignorance to which I confess.

I, too, am in the dark, yet I ask no questions. I look for comfort in the fact that Archangels share my ignorance, that Angels have not heard the explanation, and worlds do not contain it, that no prophet has espied it and no Apostle sought for it, that the Son himself has not revealed it.

The always present Son

If Christ's sonship is not eternal then the Father's identity as Father is rendered temporal too:

"But he is Father of the always present Son, on account of whom he is called Father, and with the Son always present with him, the Father is always perfect, unfailing in goodness, who begot the only-begotten Son not temporally or in any interval or from nothing."Alexander of Alexandria (in a letter to Alexander of Byzantium concerning the errors of Arius)

Thursday, May 23, 2013

When the riddles are not resolved

Powerful and humbling words from Herman Bavinck that I am grateful to have re-read:

In the case of the Christian, belief in God's providence is not a tenet of natural theology to which saving faith is later mechanically added. Instead, it is saving faith that for the first time prompts us to believe wholeheartedly in God's providence in the world, to see its significance, and to experience its consoling power...the Christian has witnessed God's special providence at work in the cross of Christ and experienced it in the forgiving and regenerating grace of God, which has come to one's own heart.Reformed Dogmatics Vol. 2: God and Creation, p. 594-5

And from the vantage point of this new and certain experience in one's own life, the Christian believer now surveys the whole of existence and the entire world and discovers in all things, not chance or fate, but the leading of God's fatherly hand.

Special revelation is distinct from general revelation, and a saving faith in the person of Christ is different from a general belief in God's government in the world. It is above all by faith in Christ that believers are enabled -- in spite of the riddles that perplex them -- to cling to the conviction that the God who rules the world is the same loving and compassionate Father who in Christ forgave them all their sins, accepted them as his children, and will bequeath to them eternal blessedness.

In that case faith in God's providence is no illusion, but secure and certain; it rests on the revelation of God in Christ and carries within it the conviction that nature is subordinate and serviceable to grace, and the world [is likewise subject] to the kingdom of God.

Thus, through all its tears and suffering, it looks forward with joy to the future. Although the riddles are not resolved, faith in God's fatherly hand always again arises from the depths and even enables us to boast in afflictions.

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

On reading Augustine

Carl Trueman's blog post and short review of Matthew Levering's The Theology of Augustine is well worth a read. Here's a snippet:

The pears incident in Book Two is, of course, the moment of Augustinian fall. For all of the emphasis on sex and sin in his work, it is the incident of petty theft which serves to show the depravity of human nature and the fall from grace.

Like that of Adam, the crime involves a garden, a tree and forbidden fruit; it involves peer pressure; it is so trivial that every reader can identify with it; it involves no motivation other than the desire to transgress a rule, to assert autonomy (divinity) in the face of established authority; and, given Augustine's coming to Christ under a tree in another garden, offers a literary device of power and beauty within the narrative which seduces the reader in manifold subtle ways.

Who can read the tale and not be drawn into the story - and into the trap - which it sets? It is a far more eloquent analysis of sin than that found in any dogmatic textbook.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

The Son, high upon his Father's throne

I once sat on a chair whose previous occupant was the Queen. I would never have dared to share that seat at the same time as Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. How much more so would it be the highest blasphemy if Jesus Christ, seated at God's right hand and ruling over the universe, were no more than a creature?

One of the Old Testament texts that dominates the New Testament skyline is Psalm 110:1. It is the Old Testament text to which the New Testament most often alludes.

There are no fewer that twenty one references, quotations and allusions to this verse in the Gospels (Matt. 22:44; 26:64; Mark 12:36; 14:62; 16:19; Luke 20:42-43), the book of Acts (2:33-35; 5:31; 7:55-56) and the Letters (Rom. 8:34; 1 Cor. 15:25; Eph. 1:20; 2:6; Col. 3:1; Heb. 1:3, 13; 8:1; 10:12-13; 12:2; 1 Peter 3:22). There is also a possible allusion in Revelation 3:21.

In Matthew 22 this text lies at the very heart of understanding the person of Christ. In Matthew 22:15-40 Jesus has faced a number of curved balls, a series of questions prompted not by a sincere desire to know the truth but with the desire to “entangle him in his words” (22:15).

After fielding these questions Jesus asks one of his own (22:42-46):

“What do you think about the Christ? Whose son is he?” They said to him, “The son of David.” He said to them, “How is it then that David, in the Spirit, calls him Lord, saying “'The Lord said to my Lord, sit at my right hand, until I put your enemies under your feet'? If then David calls him Lord, how is he his son?” And no one was able to answer him a word.

This text is key to understanding the divine identity of Christ. There are clearly two persons referred to as Lord. David's “Lord” has been exalted to God's right hand, he occupies the place of supreme authority, seated with God on God's throne. Christ is no second Lord of lower rank but shares in his Father's sovereign rule over heaven and earth.

It should not be lost on us that the category for thinking of Christ in this way was not invented by the New Testament writers. They inherited this category for understanding the supreme Lordship and divine identity of Jesus, without modification, from Jesus himself. And in Matthew 22 Jesus makes it clear that David himself held as high a view of the Christ as it was possible to hold. Jesus is Lord. It is worth pondering that David's confession, just like ours, was as a result of the work of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12:3).

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Atheism and the question of being

David Bentley Hart:

Far from draining the world of any intrinsic meaning, as many of the critics of religion are wont to claim, faith in the divine source and end of all reality had charged every moment of time with an eternal significance, with possibilities of transcendence, with a reason for moral striving and artistry and dreams of future generations.

Materialism, by contrast, when its boring mechanistic reductionism takes hold of a culture, can make even the immeasurable wonders of matter seem tedious, and life seem largely pointless.

And none of the customary post-Christian attempts to make the question of being disappear can possibly succeed: even if physics can trace all of time and space back to a single self-sufficient set of laws, that those laws exist at all must remain an imponderable problem for materialist thought (for possibility, no less than actuality, must first of all be); all the brave efforts of analytic philosophy to conjure the ontological question away as a fallacy of grammar have failed and always will; continental philosophy’s attempts at a non-metaphysical ontology are notable chiefly for their lack of explanatory power.

And this, I venture to say, is why atheism cannot win out in the end: it requires a moral and intellectual coarseness—a blindness to the obvious—too immense for the majority of mankind.From his review of Alister McGrath's The Twilight of Atheism

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

The wrong kind of God: Tolkein on religion in The Lord of the Rings

Tolkein's description of Sauron's God-complex is reminiscent of the aversion-against-God language found in Pullman, Dawkins etc.:

In The Lord of the Rings the conflict is not basically about "freedom," though that is naturally involved. It is about God, and His sole right to divine honour . . . Sauron desired to be a God-King . . . If he had been victorious he would have demanded divine honour from all rational creatures and absolute temporal power over the whole world.J. R. R. Tolkein, Letters, no. 183

But that kind of bare monotheism is as far removed from Trinitarian thinking as night is from day. The Christian God is not an oppressive tyrant in the mould of Sauron but a Being in Communion, a community of love. Self-giving lies at the heart of the divine identity, and therefore at the heart of the universe.

Sunday, January 20, 2013

One Ring to rule them all: Le Monde interviews Christopher Tolkein

Here's a snippet from Le Monde's interview with Christopher Tolkein, son of J.R.R. Tolkein:

Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time," Christopher Tolkien observes sadly.

"The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away."You can read the rest here

Saturday, January 19, 2013

A Skin Full of Chemicals (Part 2)

The atmosphere, expected and

unwelcome, enveloped him. The smell of heated,

sinking putrefaction; cloying, disturbing, suffusing itself into every pore,

clinging to every garment, a portent and foretaste of the grave’s greater

appetite to undo the vitals of life. The

stench of sores, of infection, of ageing skin, of decomposition already working

in the depths of the organs and forcing itself out, of dental rot.

When John returned home he

would furiously shower and scrub to remove the lingering odour of the

place. He glanced around the room to see

a thinning number of shrunken, withered, human beings; of people embedded in

permafrost. Their years having drawn

nigh, the make-up of homo sapiens was

slowly, inexorably, being stripped away.

This was a charnel house for the living, a parlour furnished for those

enduring a double death.

The experiences of close

relatives followed a familiar pattern.

Like a wound that never healed, each visit brought back the visceral

awareness of first losing them in the consuming fog of dementia. The memory of a life irretrievably lost, as

the fragility of mind and will found no escape from the ineluctable reach of

this preternatural shroud, abided as a mournful presence in the room.

At times the pressure of this

sadness seemed so great, so palpable, it was as if the room would soon totter

and collapse under the weight of it. John

now belonged to the ranks of those who came to watch and wait for the body to

give way. He shared in this futility,

belonged to a fellowship of fellow sufferers, knew their sense of emotional

exhaustion and used up grief, and

counted down to the moment when a strange sense of relief would inevitably come. But although his experience was not a-typical

there was about his demeanour, as any health professional and close observer of

human behaviour could see, an element of detachment more akin to indifference

than to weariness.

A single thread, delicate as

gossamer, held him to this place; a bond of nature tightly anchored, wearing

thin, biologically weakening. Across

the room, amid the grotesque forms of what looked to him like so many animated

cadavers sat listlessly on chairs, stood his father.

A tall man in his prime, he

had begun to bow and stoop. Equine like

strength having left him, his ill-fitting clothes hung loosely upon his rigid,

calcified frame, giving him the resemblance of a badly dressed weather worn scarecrow. His skin was sallow. His pock marked face sported a day’s growth

of greying stubble. The eyes were as

bloodshot and hollow as a drunk’s.

Vacant holes, bereft of the power of recognition.

The lower lip glistened and protruded

with a childlike defiance, bearing the sullen aspect of one whose ambitions had

been curtailed by a superior force. He

was diminishing with every grain of sand that passed through the aperture of an

egg-timer. It was hard not to pity him,

not to pity what he had become, what he had been contorted into by the downward

drag of this mental illness.

But there was a darkly comedic

element to his appearance, an inappropriate adornment that struck a note of

sick humour. As a result of repeated

bumps, scrapes, and falls, his wakening hours forced upon him the wearing of padded

head gear that made him resemble an amateur boxer. Without his knowing it George Daniels cut a

tragic, pathetic, risible figure. He was

now a parody of the man captured in the photographs in his son’s home.

“Come on now George, your boy

is here to see you”

“Who?”

“Your son, John”

“I’ve got a son?”

“Yes George. He’s come to see you”

“I’ve never seen him before”

“Yes you have George

“Have I. Oh.

That’s nice. Is that him? What’s he here for? Has he been to seen me before?”

“Yes George”

“Why is he here now? What does he want?”

“Come one now George, he

always comes to see you”

This patient, reassuring note,

daily struck in the tone of the staff nurse seemed illimitable. It always did. Her voice had in it a perpetual calmness,

never once betraying a hint of anger, of annoyance. Where did that kind of patience come

from? Was she born with it? Was it a gift? Was it cultivated? Was it simply a fake professional demeanour,

a façade concealing an interior of impersonal indifference?

Friday, January 18, 2013

A Skin Full of Chemicals (Part 1)

This is an experiment. A piece of fiction. The beginnings of a novel...

Where do we come

from?”

“What are we?”

“Where are we going?”

John

Daniels sat at a forward angle on the scuffed brown plastic chair in the

Visitors Room of the Dementia Ward at St. David’s Hospital. The low chatter of day-time television, with

its seemingly ubiquitous stream of banalities, the same banalities that rolled

and reproduced themselves into the small talk of the nursing staff and the two

other visitors in that cramped, unpleasant room, hindered any possibility of

gathering together his thoughts. He had

been sat there for a full hour and twenty minutes, his throat and eyes dry from

the permanent stifling atmosphere of the place.

He dipped his hand into his rucksack and rummaged around for some

painkillers lodged somewhere between the clutter of exercise books he’d vainly

attempted to mark. There was an inch or so of lukewarm mineral water left in

the bottle, just enough to wash down the last couple of tablets. From as far back as he could remember the

effort of swallowing the second tablet always brought with it a retching

sensation, a reflex that persisted all the way to his forty-fifth year.

Tension headaches were to be

expected at this time of year as the steady stream of teaching and marking

swelled to a cataract. He held his palms

against his temples and massaged them gently and rhythmically. His eyes eventually scanned the sun bleached

sheets of paper hanging from the cork-board enough times for them to irritate

him with their child-like script, and seemingly unselfconscious display of

ignorance in the small matters of punctuation and spelling. But when your eye has been trained to assess

academic work, errors and mistakes can’t help but stare blankly back at you

every time you gaze at a text. Those outdated

messages and memos, whose fading legibility formed a written residue of what

was once important, insistent, relevant, needlessly hung there. Mistakes mingled in an intelligible code

expunged of any usefulness.

“He’s awake. You can see him now.”

At the soft tones of the staff nurse John stood,

discordantly scraping the metal legs of the chair on the worn, cracked, tiles

of the Visitors Room floor and followed her into the Day Room.

“How has he been?”

“Quite bright these last few

days. His sleep has been restful.”

He wondered whether the restfulness owed itself principally

to an upping of medication. No more

words were exchanged between them. The

soft padding of their feet was the only sound as they briskly moved down the

corridor.

Crossing the threshold of the

Day Room was like entering another world.

This was another world. Mentally

he always checked himself and, with conscious effort, adjusted his perspective,

as he shifted hemispheres from his native environment of a bustling High

School, a life of domestic comforts and

unease, of long worn and much loved social routines, to this asphyxiating

domain of human deterioration and unravelling.

The room itself was sparsely

furnished. The décor of pastel shades,

of hospital bedside chairs pressed into service as casual lounge furniture, of

an assembling of largely kitsch reprints of paintings by vaguely familiar

artists – the kind only ever found on institutional walls – gave the impression

of a contrived, makeshift, artificial homeliness.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

God and wish fulfilment (1)

We owe the assertion that God is merely a projection of human attributes on a cosmic scale to Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872). Having no objective existence, God was no more than make believe, the result of wish fulfilment. Perhaps the 21st Century gloss would be to stress that it is an infantile wish, cherished by the intellectually immature, and worthy of being mocked.

De Lubac's The Drama of Atheist Humanism has a helpful summary of the 19th Century dismantling of Christian belief:

As Strauss tried to account historically for the Christian illusion, Feuerbach tried to account psychologically for the religious illusion in general, or, as he himself put it, to find in anthropology the secret of theology.

The substance of what Strauss said, in his Life of Jesus (1835), was that the Gospels are myths expressing the aspirations of the Jewish people. In Religion Feuerbach was to make the parallel assertion that God is only a myth in which the aspirations of the human consciousness are expressed. "Those who have no desires have no gods either...gods are men's wishes in corporeal form." (p. 27)

For Feuerbach, then, God is only the sum of the attributes that make up the greatness of man. (p. 29-30)Feuerbach's assertion had a powerful impact on his contemporaries. Engels said that "we all straightway became Feuerbachians." But it was an assertion all the same.

Does Feuerbach's assertion help us to assess whether the wish, or desire, for God originates solely in human experience? Does it rule out the possibility that it has been implanted in us by a divine hand? If so, how exactly? Is it a given that presupposes atheism on other grounds to gain traction or to pass off as an argument? The existence of the wish for God is one thing, the explanation for it is, after all, another. The wish does not prove that what we desire does not exist.

C. S. Lewis replied to Feuerbach's position by arguing that the most probable explanation for the existence of a desire that no experience seemed to satisfy was the fact that we are made for another world. Is there anything in Feuerbach's assertion that would invalidate Lewis' response?

Can some religious views be ascribed to projection? Of course. Does that demonstrate the universal validity of Feuerbach's assertion? Hardly. Unless of course we think it is permissible to lump all religious views together without making any distinctions. But a case has to be made for that.

Can atheism's denial of God be interpreted as an inversion of Feuerbach's assertion? In the flight from God could some atheists be driven by a desire to escape from accountability of their actions? Alister McGrath's example of this (from memory, I've not read his book on apologetics since 1996) is that of a Nazi concentration camp guard who denies God in order to evade being judged.

The wish for a Godless universe does not prove that God does not exist. But neither Feuerbach's view of God as wish fulfilment, nor the rejoinder about evading God, is necessarily true. Both positions are assertions relying on actual arguments and evidences.

Feuerbach the atheist evangelist

Sometimes atheists have the same passion for preaching and conversion as evangelicals.

Here is Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), towards the end of his life, oozing with missionary zeal, as he calls men and women to repentance (stop being religious and worshipping God), and faith (in generic human nature):

The goal of my work is to make men no longer theologians but anthropologists, to lead them from the love of God to the love of men, from hopes for the beyond to the study of things here below; to make them, no longer the base religious or political servants of a monarchy and an aristocracy of heaven and earth, but free and independent citizens of the universe.(Quoted in De Lubac The Drama of Atheist Humanism, p. 33, n. 39)

And then along came Marx, and Lenin, and Stalin, and all that plausible rhetoric about freedom lay beneath an iron curtain. If you want to know how that worked out then read Solzenhitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Is Christianity bad for human identity?

In The Drama of Atheist Humanism Henri De Lubac draws a contrast between the reception of Christian anthropology in the ancient world and its rejection almost eighteen hundred years later during the rise of modern atheism. What once was liberty, the view of human identity in the image and likeness of God, a creaturely identity that gave dignity and worth to humanity, came to be seen as a form of oppression.

De Lubac articulates the emancipating force of the Christian doctrine of man:

From the outset that idea had produced a more profound effect. Through it, man was freed, in his own eyes from the ontological slavery with which Fate burdened him. The stars, in their unalterable courses, did not, after all, implacably control our destinies.

Man, every man, no matter who, had a direct link with the Creator, the Ruler of the stars themselves. And lo, the countless Powers--gods, spirits, demons--who pinioned human life in the net of their tyrannical wills, weighing upon the soul with all their terrors, now crumbled into dust...But with the rise of what the 19th Century French philosopher and politician Proudhon termed the "humanists" or "new atheists" the freedom of the Christian view of humanity was rejected. Again De Lubac summarises:

Man is getting rid of God in order to regain possession of the human greatness that, it seems to him, is being unwarrantably withheld by another. In God he is overthrowing an obstacle in order to gain his freedom.Was it a fair exchange?

Did the perspective of seeing people as no more than a skin full of chemicals enhance human dignity?

Did it usher in compassion instead of cruelty?

Did the abandoning of the imago dei lead to an era where the weak and infirm, at the beginning and end of life, received more protection?

De Lubac got it exactly right. By extinguishing God the modern atheistic humanists found that "exclusive humanism is inhuman humanism":

It is not true, as is sometimes said, that man cannot organize the world without God. What is true is that, without God, he can ultimately only organise it against man.

Christianity: Almost an illusion

If God has not spoken, if he has not revealed himself, then Christians would be in agreement with atheists. The whole thing would then be a pious fraud, a psychological exercise in wish fulfilment, a colossal sham and masquerade.

Far from this being a fact unknown to believers it is spelled out clearly by the great Dutch theologian Herman Bavinck:

With the reality of revelation...Christianity stands or falls.

As science never precedes life, but always follows it and flows from it, so the science of the knowledge of God rests on the reality of his revelation. If God does not exist, or if he has not revealed himself, and hence is unknowable, then all religion is an illusion and all theology a phantasm.Quoted in Avery Dulles Models of Revelation, p. 5

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)