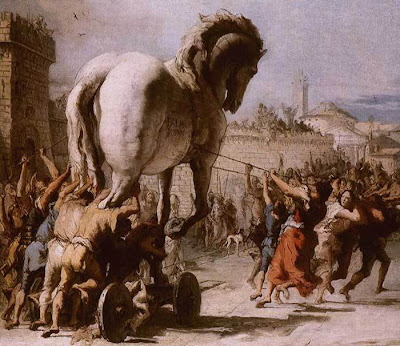

One of the things that you are taught on your first driving lesson is that there is a blindspot over your right shoulder. No matter how often you check your mirrors there is an area that is hidden from view. Ignorance of that blindspot has the potential for causing accidents. It is like that with sin. We can deceive ourselves that our actions are acceptable in one area, and our consciences are clear, but lurking in the blindspot are thoughts, attitudes and even actions that are dishonouring to the Lord. This may well be the case in our zeal for the truth in the context of controversy. Engaging in polemics can blind us to our own sins. That we can sin in this way should come as no surprise to us. After all there is no other situation that we experience where we are free from temptation. And when engaging in controversy there are particular sins that we will face.

One of the things that you are taught on your first driving lesson is that there is a blindspot over your right shoulder. No matter how often you check your mirrors there is an area that is hidden from view. Ignorance of that blindspot has the potential for causing accidents. It is like that with sin. We can deceive ourselves that our actions are acceptable in one area, and our consciences are clear, but lurking in the blindspot are thoughts, attitudes and even actions that are dishonouring to the Lord. This may well be the case in our zeal for the truth in the context of controversy. Engaging in polemics can blind us to our own sins. That we can sin in this way should come as no surprise to us. After all there is no other situation that we experience where we are free from temptation. And when engaging in controversy there are particular sins that we will face. Before getting to the main part of the argument there are some preliminary matters to bear in mind. Those who vocalise concern over false doctrine are of course an easy target. There is a consistent, and quite inaccurate, typology at work in these debates. There is the stigma attached to those who seek to defend the truth of being branded unloving, ungracious, narrow, harsh, and even schismatic. Strong words about error are not allowed in the contemporary Church. But that itself is a narrow-minded view, far narrower than the Bible. Rather ironically those who criticise a right concern about orthodoxy and heresy are themselves, at times, objectively guilty of the very thing they deplore.There is here a forest of rhetoric that needs cutting down so that intelligent debate about opposing positions can be dealt with fairly and without party spirit.

Then there has to be room for Paul's responses to the Galatian and Colossian false teachers, and Christ's words to the Pharisees and teachers of the law. I'm sure that it is possible for us to be strong on condemning error and yet to be humble at the point of assessing the reasons for our own right understanding--at the same time. Whether we are guilty of pride in our own orthodoxy is a matter to search our own hearts about. It isn't something that can be read off automatically and infallibly whenever we see someone become angry because of destructive heresies or raise their voice about winds of doctrine.

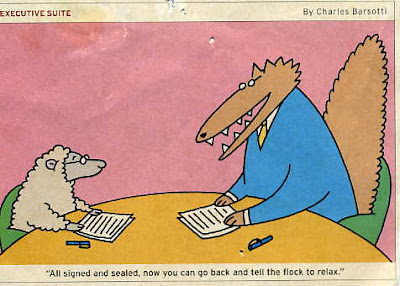

But although sinful attitudes are far from synonymous with condemning error they are not totally unavoidable. Consider Francis Schaeffer's description of the sins in the blindspot:

“Thus whenever it becomes necessary to draw a line in the defense of a central Christian truth it is so easy to be proud, to be hard. It is easy to be self-righteous and to self-righteously think that we are so right on this one point that anything else may be excused— this is very easy, a very easy thing to fall into. These mistakes were indeed made, and we have suffered from this and the cause of Christ has suffered from this through some fifty years.”

We can examine ourselves along these lines both positively and negatively:

1. What graces am I expected to display when I am dealing with theological opponents?

2. What attitudes and actions am I to avoid when dealing with those in error?

Paul takes this two-fold approach in 2 Timothy 2:23-26:

“Have nothing to do with foolish, ignorant controversies; you know that they breed quarrels. And the Lord's servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness. God may perhaps grant them repentance leading to a knowledge of the truth, and they may escape from the snare of the devil, after being captured by him to do his will.”

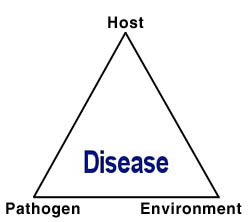

Opponents of the gospel are in a desperate spiritual situation. Is there any hope for them? Maybe the Lord will grant them repentance so that they will come to know and believe the truth. Until, or unless, that happens they are ensnared by the devil. Failure to think in these categories seems to be the cause of the ungodliness that can exist on the part of the defender of the gospel. We need an approach that takes in view the people we are dealing with, the doctrinal position that they hold, and the predicament that they are in. Toward the person in error we are to show kindness. Toward their doctrinal position we are to skillfully expose it as error and correct it. Toward their predicament we are to show compassionate understanding, prayerfully asking God to deliver them.

Right belief of the gospel, true saving faith, is a work of grace. There is no room here for pride in our rightness but rather thankfulness for God's mercy. Who, after all, has made us to differ? What do we have that we did not receive? Patience, gentleness, kindness, and a refusal to be quarrelsome are the fruit of consciously knowing that there is a great spiritual battle going on. It is not only the doctrines of grace that we are to be thankful for but we must, in prayer and praise, thank God for his grace in giving us the knowledge of the truth. We ought to reflect on the Lord's goodness in giving us understanding. This is because of his grace alone. John Newton provided solid counsel from Paul's words here:

“If, indeed, they who differ from us have a power of changing themselves, if they can open their own eyes, and soften their own hearts, then we might with less inconsistency be offended at their obstinacy; but if we believe the very contrary to this, our part is not to strive, but in meekness to instruct those who oppose.” (From John Newton's Works, Letter XIX, On Controversy).

They are culpable since they have chosen to embrace error, but they are also deceived. Now, what else but knowing that a change of heart is something solely God given can temper the approach of the polemicist? What other explanation is there for patience and gentleness as appropriate dispositions? Coming to a knowledge of the truth has never been self-generated. Calvin wrote in his commentary on these verses that “when we remember that repentance is God's gift and work, we shall hope the more earnestly and, encouraged by this assurance, will give more labour and care to the instruction of rebels”.

Such gentleness and patience should not be confused with moral weakness and softness. Paul's words here are consistent with those he wrote to Titus on silencing the false teachers, rebuking straying believers sharply, and after two warnings having nothing to do with divisive people (Titus 1:10-16; 3:9-11).

The following quotation from John Owen has been a treasured favourite of mine for many years. I first came across it in Packer's Among God's Giants (a must read in itself) and quoted it from Packer's work when I wrote a chapter on preaching for Keeping Your Balance (Apollos/IVP, 2001). But knowing the context of the quote makes its impact on my thinking even greater. It comes in the penultimate section of Owen's introduction to Vindicae Evangelicae, his massive refutation of the Socinians (Volume 12 in the Banner edition). That he should write like this in the introduction to a polemical book shows me all the more what must be at the heart of contending for the faith in a way that pleases God. The three questions that he asks give the game away as to the identity of his opponents. But they are great questions to ask whenever we may need to contend for the gospel. Owen has not only a weapon in his hand, for the pulling down of the Socinian anti-gospel stronghold, but a plea for grace in the heart of all those who fight for the glory of God:

"When the heart is cast indeed into the mould of the doctrine that the mind embraceth; when the evidence and necessity of the truth abides in us; when not the sense of the words only is in our heads, but the sense of the things abides in our hearts; when we have communion with God in the doctrine we contend for, --then shall we be garrisoned, by the grace of God, against all the assaults of men. And without this all our contending is, as to ourselves, of no value.

What am I the better if I can dispute that Christ is God, but have no sense or sweetness in my heart from hence that he is a God in covenant with my soul?

What will it avail me to evince by testimonies and arguments, that he hath made satisfaction for sin if, through my unbelief, the wrath of God abideth on me, and I have no experience of my own being made the righteousness of God in him,--if I find not, in my standing before God, the excellency of having my sins imputed to him and his righteousness imputed to me?

Will it be any advantage to me, in the issue, to profess and dispute that God works the conversion of a sinner by the irresistible grace of his Spirit, if I was never acquainted experimentally with the deadness and utter impotency to good, that opposition to the law of God, which is in my own soul by nature, with the efficacy of the exceeding greatness of the power of God in quickening, enlightening, and bringing forth the fruits of obedience in me?

It is the power of truth in the heart alone that will make us cleave unto it indeed in an hour of temptation.

Let us, then, not think that we are any thing the better for our conviction of the truths of the great doctrines of the gospel, for which we contend with these men, unless we find the power of the truths abiding in out own hearts, and have a continual experience of their necessity and excellency in our standing before God and our communion with him." (John Owen, Vindicae Evangelicae, p. 52).

Here is a snapshot from the end of the life of Charles Hodge. Hodge died in the June of 1878, having taught for over fifty years at Princeton Seminary. In the April of that year Hodge had addressed the Sabbath Afternoon Conference on "fighting the good fight of faith" from the words of the Apostle Paul to Timothy (1 Timothy 6:12). David Calhoun summarises Hodge's address:

Here is a snapshot from the end of the life of Charles Hodge. Hodge died in the June of 1878, having taught for over fifty years at Princeton Seminary. In the April of that year Hodge had addressed the Sabbath Afternoon Conference on "fighting the good fight of faith" from the words of the Apostle Paul to Timothy (1 Timothy 6:12). David Calhoun summarises Hodge's address: