Augustine is regarded as a kind of a bogey man by some for his movement away from identifying Old Testament theophanies as manifestations of the incarnate Christ, breaking an interpretative tradition that extended from Justin Martyr on.

Augustine was hardly unaware of this tradition (De Trin. Book II:2:8):

Take some words spoken by God in one of the prophets: Heaven and earth do I fill (Jer. 23:24); if they are ascribed to the Son--and it is he, so a number of authors prefer to think, who spoke to and through the prophets...

There is even a prophecy of Isaiah in which Christ himself is to be understood as saying about his future coming, And now the Lord, and his Spirit, has sent me (Is 48:16)

Why then the departure from this tradition?

Is it as crude as the accusation made by the late Colin Gunton that an

'anti-incarnational platonism is to be found in Augustine's treatment of the Old Testament theophanies'?

Gunton was sharply critical of Augustine on this point. The breach with the tradition was emblematic of a deeper theological fissure opening up between the relationship of the creature and the Creator, a widening that has serious implications for taking Augustine as a reliable theological guide on the trinity at all:

In place of the tradition, going back to Irenaeus, of the Father relating to the world by means of the Son and Spirit, we are in danger of supposing an unknown God working through angels. Augustine's shying away from the involvement of God with the material order should be contrasted with the more concrete modes of speech of both Irenaeus and Tertullian.

'Augustine, the Trinity and the Theological Crisis of the West' in

The Promise of Trinitarian Theology, p. 34-35

But for Augustine

'divinity cannot be seen by human sight in any way whatever' (De Trin. Book I:2:11), and therefore he was sensitive to the view that invisibility was predicated only of the Father, and not of the Son. The invisibility of the Son, connected as it is with his essential divine nature, is something that Augustine was zealous to safeguard. In fact there may be some evidence that this theological lacuna, namely that of the invisible Father and visible Son, stemmed not only from the tradition but also, and perhaps more pertinently so, from the Manichaeism that Augustine had escaped from.

Furthermore, Augustine wanted to do justice to the primacy of the biblical language of 'sending' and 'sent' being tied to the historical reality of the incarnation, and not to previous manifestations and theophanies.

On other matters, such as whether and how we can identify particular persons with particular theophanies (after all, aren't the outward signs at Sinai also evident at Pentecost? Could not the Spirit have therefore manifested his presence at the giving of the Law?), Augustine was prepared to be agnostic if the evidence was not persuasive enough.

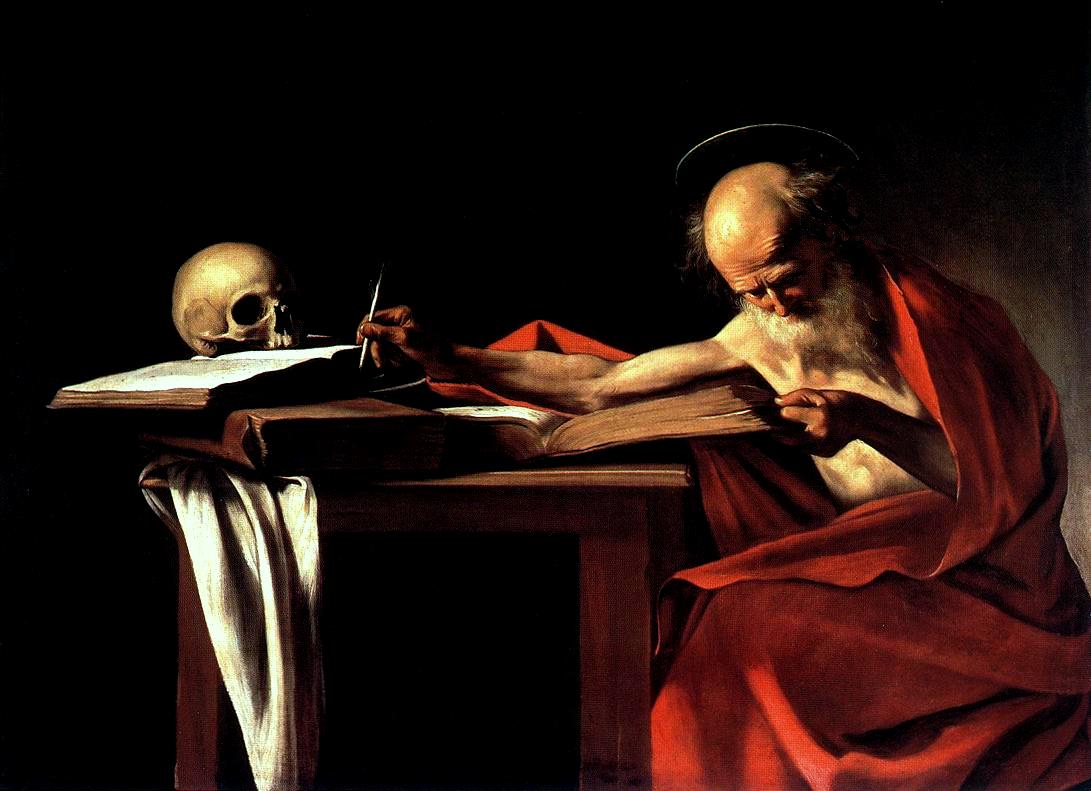

Sorting out what the great bishop and doctor of grace called

'this tangled question' of the persons manifested in the Old Testament theophanies is something that I will defer to later posts. It would be a great help to find out whether Augustine paid any attention to the ghost of Plato looking over his shoulder as he wrote, and, as ever, it is best to assess him based on his own words as he unfolds his case.